Chapter 3 Success in Analytics

There I (Ashutosh) was. The smell of the strawberry slushy sweetened the whole atmosphere. You could feel the heat of the day with your bare toes, but thankfully the water fountains and rides made it fun. Yes, I was at a water park with my kids, of course, because it would be kind of weird to be there by myself. All the kids were having fun except for one little girl with ponytails in a Nemo suit. I overheard her discussion with her mom. The mom looked at the daughter and said, “You cannot play with those water balloons here.” And the daughter, without even thinking for a second, looked up at mom and said, “Says who, mom?” I was very puzzled because she wanted to know “who” and not “why?” Is this a problem we face as a society, or even worse at work: that we make our decisions based on authority and not the reasons behind them? That we do not ask “why” but “who” and “how”?

In this chapter, let’s talk about the three P’s of success — products, people, and passions. If you follow them closely, you’ll double your success.

I believe your success is deeply rooted in the three P’s, which are deeply rooted in “why”. The premise is simple: analytics is not really about analytics, but it’s the action that happens after the analytics. Action must follow analytics, for your success is defined in that action.

Let’s look at the first P: Products.

3.1 Products

Products are what people care about. Have you played Minecraft®? If so, you know that it’s neither polished nor realistic like, say Call of Duty®, but it’s still successful. In fact it is so successful that it has sold more than 121 million copies, and Microsoft purchased the game for $2.5 billion.

What’s the reason for its success?

Well, I believe it’s successful because it’s a product that people care about. It is simple by design, but you can build a world that’s truly yours. You can live in your incomplete dreams and fulfill them — and that is something people will care about it.

How do you go about building something that your users will care about? There is no doubt that you have to develop your craft.

In his book Talent is Overrated, Colvin (2009) talks about a wide receiver from a small school who ran a 40-yard dash in 4.69 seconds. To give you some perspective, most of the NFL prospective recruits complete the 40-yard dash in 4.5 seconds or less. We know that in NFL even 0.01 seconds is a lot and he wasn’t even close. It is no wonder that the NFL teams were apprehensive about his performance, but since he was so well known, one NFL team did eventually select him. He then went on to play twenty years of professional football. Can you believe it? Twenty years of professional football and he broke all sorts of records. Do you know who that was?

His name is Jerry Rice.

How did he achieve something that seems so humanly impossible?

In the off seasons, he had a six-day workout. He used to run five miles on a hilly trail every day and then come back and do strength training. Others tried to join him but got sick before completing the training by the end of the day.

I have no doubt that with deliberate practice you can build a craft that’s way above average.

I have seen many people who say they want to do analytics, but have done nothing deliberate to develop that craft. Why would anyone take you seriously if you are not serious about your own craft? This book will help you sharpen your craft, but we know that most people won’t even finish reading it, let alone practice the code in it8. Don’t be most people.

Let’s say you worked hard and developed your craft. What’s next?

You build products that solve problems but the problems should be important enough to warrant a solution. An example: the Square™ credit card reader. Square™ credit card readers solve a very important problem and its accessibility and ease of use are what make the product unique. Other people will solve problems which are unimportant and create products that nobody cares about. A good example of a product that didn’t solve any real problem is the LinkedIn network map. It didn’t provide any new information; LinkedIn realized this and retired the product.

Again, don’t try to solve a problem which is not a problem for your users. Only pick problems that you think would have some merit and the users would care about.

Let’s say you develop your craft; you know some of the products that you want to develop. Where do you go from there?

Here’s a paragraph from Alice in Wonderland:

Alice: Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here? The Cheshire Cat: That depends a good deal on where you want to get to. Alice: I don’t much care where. The Cheshire Cat: Then it doesn’t much matter which way you go.

Don’t be a wanderer. Plan and then do. Don’t just start walking in the wrong direction. To plan better you can use a tool called an “activity systems map.” This tool helps you define your strategy.

I’m kind of finicky about various things. But one particular thing I don’t like in particular is when people use buzzwords like “strategy”" and “innovation.”

One day I heard that some departments were being named “strategic” something. Why would you name your department ‘strategic something’? Would you do anything that is not strategic?

But I really wanted to understand what strategy is. I read many books and articles, but I still didn’t understand it.

Until one night.

My son, who was 6 years old then, walked into my room and said, “Dad, could I sleep in your room?” And, like any loving parent would do, I sent him back to his room. Then he went to his younger brother, who was 4 years old, and asked him to join in asking me if they could both sleep in my room.

To his disappointment, the younger one said no.

The older one thought for a minute and said, “But what about the dark shadows you see in the window?”

With that, not only did I understand what strategy was, but I also understood that you don’t let your kids talk to each other for more than 10 seconds when it’s past bedtime. Because then I had to explain to the younger one that he didn’t have to worry about any shadows.

What is strategy then? As my son taught me, strategy is planning some deliberate steps to create a sustainable advantage to overcome your competition.

The actions, the steps that you take, are not strategy. They are part of the strategy. Strategy is your “why” and action steps are your “how.”

This activity systems map [Note: We can’t reproduce the map here due to copyright issues, but you will easily find the map with a simple search] is from Michael Porter’s classic paper “What is strategy” (Porter 1996). You can also find this activity systems map in Stadtler (2015)’s paper.

Porter shows how IKEA was able to create its strategic position and align all the actions around it. IKEA’s strategic position was to provide affordable furniture to young people. Notice the dark circles. Those are the core pillars of their strategy, providing limited customer service, self-selection by customers, modular design, and low manufacturing cost. Notice the text “suburban locations with ample parking” that’s sitting in between “self-selection by customers” and “limited customer service.”

That’s how you create strategy and a plan.

Using this as an inspiration, you can develop one for your organization.

GG+A shared this idea in a presentation. This is the analytics road map as shown in Table 3.1. The first thing you have to remember is what your are you goals and results. To become the best at something is not a goal; it is a result. Once you identify your goals, you outline all the steps that you have to take to get to that goal, you put a timeline on it, and lastly, you find partners. It could be a short-term goal or a long-term one Don’t feel that you don’t have all the resources to pull this off. If you start planning right now, in few years, you can go wherever you want to go and create your vision.

| Goal | Short Term | Long Term | Partners | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good data | Standardize addresses | Acquire newer data | Advancement Services and fundraisers | Trust in data |

| Stable IT/Reporting infrastructure | Produce standard reports | Allow complicated reporting | Advancement Services and IT | Trust in data and reliable reporting |

| Analytics infrastructure | Run simple models | Combine reporting and modeling | Advancement Services and IT | Start of data driven decision making |

People ask me “Why so much emphasis on process? Why so much emphasis on thinking? I’ve even had some employees who pushed me hard on this. Think about this for a second. If something is easy to do, then it is very likely that it will be replaced by some programs. What organizations cannot afford to lose are thinkers—thinkers who provide valuable actions, valuable insights, and recommendations.

Don’t be a commodity.

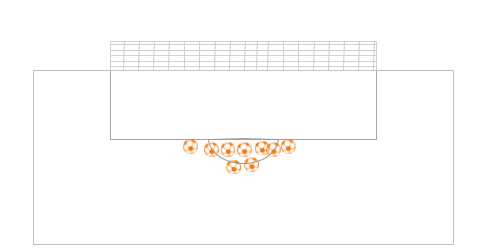

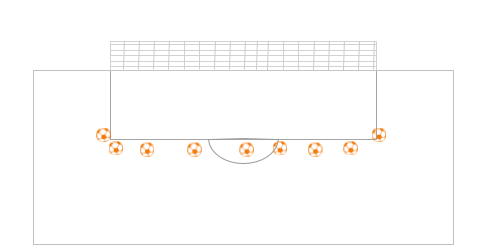

In Figure 3.1 and 3.2 we have two kickers, Kicker A and Kicker B. Let’s say you’re the head coach of the team. Which kicker would you choose for your next game and why?

FIGURE 3.1: Mean and variance of kicks: Kicker A

FIGURE 3.2: Mean and variance of kicks: Kicker B

You see that both of kickers are kicking the ball in, but the spread is really high for Kicker B. If you’re a leader, you always want Kicker A, who is doing consistent work and hitting the targets all the time. But if you want innovation, you want variance, and variance is your friend9.

You have to be at the edge of various fields that give you this inspiration. You try fifteen or twenty different solutions. You will fail 99% of the time, but you will strike gold in one. This can only happen when you are not relying so much on consistency and reliability. You have to give yourself the freedom to innovate.

What do you do once you have your ideas ready, have great products, and have developed your craft? You, of course, go and develop that product, right?

No.

You actually develop the most minimal version possible and you test it with your users. See whether they even care about it. See whether they even like those features. Maybe they want the same information but in a different format. But unless they tell you what they want, you will be producing something that nobody cares about.

This is called a Minimally Viable Product (MVP). You develop the smallest version possible that’s still workable and demonstrates what you want to do.

Once you have your MVP, you have everything, and everything should go well, right?

Well, no, that’s the second P: People.

3.2 People

It doesn’t matter how good your models are or how accurate your theories are. If people don’t understand you, if they don’t trust you, if they don’t get you, then your models or your accuracy aren’t worth much.

How do you get them to do something? How do you make them take action?

C. Heath and Heath (2007), in their book Made to Stick, compare a CEO directive of “let’s maximize shareholder value” to President John F. Kennedy’s call of “landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.”

Which one is clearer? Which one provides vision?

As the Heath brothers say (2007), simple ideas stick easier than complicated ideas. They also refer to simple ideas as clearing the path for better adoption, removing all the obstacles so people can take action. Try to remove all the obscurities around the idea and just communicate the core themes.

“Perfection is achieved, not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.”

— Antoine de Saint-Exupery

That’s where data science proves useful. Not only are you creating models that are useful, but you are also creating accessible ways to consume information to drive action.

Here’s another example to explain the “stickiness” of a concept:

What do you think of when you think of Einstein? E = mc2? What do you think of when you think of Richard Feynman? Unless you are a student of physics or a Feynman fan, most likely nothing.

Why do we remember Einstein? That equation is simple to remember. Of course, simple doesn’t mean trivial.

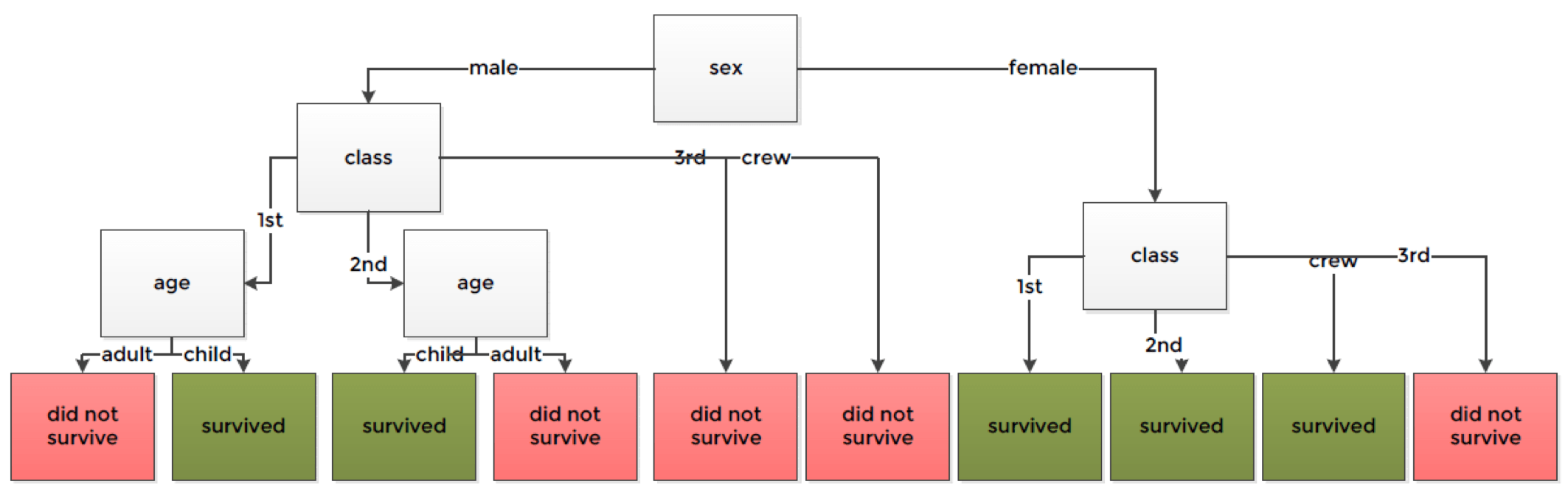

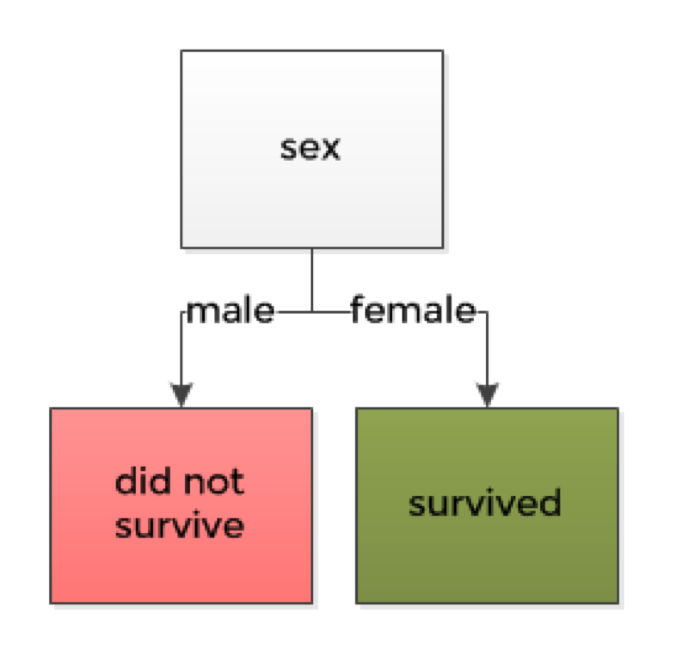

A good example of how simple performs well is shown in Figure 3.3, which shows a decision tree with the Titanic data. It uses pink boxes to show who did not survive on the Titanic and green boxes to show who did survive. The decision tree model in this case shows with 78% accuracy that boys and females from higher classes survived. This tree is explainable.

FIGURE 3.3: Bigger decision tree with 78% accuracy

But did you know that there is an algorithm called oner? As its name implies, it generates only one rule, yet it has 77% accuracy! As Figure 3.4 shows, you can conclude that females survived and males did not survive.

FIGURE 3.4: Smaller decision tree with 77% accuracy

You may think that this is too simple to perform, but Holte (1993) compared many data sets and many techniques and found that the oner algorithm performed equally or slightly worse than other state-of-the-art algorithms.

Even if you don’t want to buy into this, that’s okay, but at least use this as your baseline to compare and try to outperform this model.

But remember, two to three percentage points of accuracy don’t matter much if you are losing all the explanatory power of the model.

What do you do once you simplify your products?

Well, to get people to take some action, you have to understand their needs as well.

One day I asked my then six-year-old son, “Why don’t you write the grocery shopping list?” He looked in the fridge and he looked at the fruit basket. He wrote a few things down and gave me a list. I was so proud and I started reading. He had listed “apples, bananas, oranges, milk, juice, toy, and candies.”

I realized his needs were completely different from my needs, and his perspective on grocery shopping even more different. Unless we understand the biases, the needs, and the perspectives, what we think could be helping others could actually be hurting them.

But, say, we do everything, but they still don’t take action. What do we do?

You may have a better chance if you understand the principles of persuasion and influence. There are two simple techniques that could work really well.

The first is social proof. We all know what social proof looks like: every Amazon® review you read or the canned laughter you hear in the sitcoms (Amblee and Bui 2011; Bore 2011).

Social proof is pretty straightforward. How do you get that into action? You must find a willing partner and provide outstanding results. Then you ask that person to speak about your results. This can create momentum, carrying the message to other people, and removing the inertia. That’s social proof.

The second is foot-in-the-door or smaller commitments.

In his book Influence, Cialdini (1987) explained the foot in the door principle with an example. A few volunteers went to two groups of homeowners. To one group they said, “We want you to put this huge public service announcement billboard on your lawns.”

This idea was so crazy that 86% of the people did not agree to put up a billboard. But in the other group, 76% of the people agreed to that crazy idea.

What do you think was different? Three weeks prior to being asked, another volunteer went to the same homeowners and asked them to put a three-inch sign that said, “Be a safe driver” on their lawns. Because they agreed to this simple idea, three weeks later, they agreed to this crazy idea, 76% of them.

You may ask yourself, “Isn’t this book about data science?” Why are we not talking about analysis then?

We will get there, but let’s look at one more thing first.

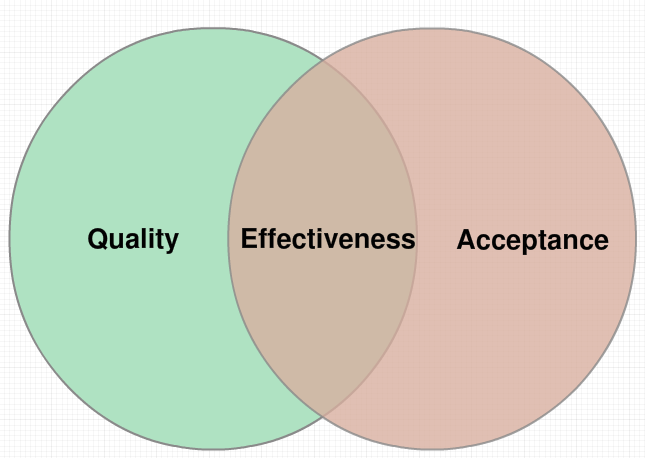

Jerry Allyne, former vice president of strategic planning and analysis at Boeing Commercial Airplanes, spoke about the fantastic Venn diagram seen in Figure 3.5. This is a simple tool, but it has helped me realize that it’s not really just about analytics.

Jerry described this diagram further using the change effectiveness equation (see Voehl and Harrington 2016, 6:65). Let’s say the quality of analysis is Q and its acceptance is A. The overall effectiveness is the combination of both factors:

E = Q X A

FIGURE 3.5: Quality, acceptance, and effectiveness (Jerry Allyne, INFORMS presentation)

He explained this further. Let’s say we give a maximum of 10 points to both quality and acceptance. Therefore, the maximum effectiveness is 100.

Say you built a really fantastic model and you said to yourself, “I’m so proud of this model. I deserve a 7 on quality.” But while you were working on this, you didn’t talk to people, and thus the acceptance was only three points.

Your total effectiveness:

7 X 3 = 21

Since you were disappointed, you worked harder and built an even better model. You gave yourself an 8 on quality, but the acceptance stayed the same.

The total effectiveness still did not go up.

8 X 3 = 24

Then you realized, “You know what, I’m not going to worry about increasing the quality. I’ll meet people for coffee. I’ll understand their needs. I’ll explain to them how analysis could really be helpful to them.”

Now your acceptance went up and you got 6. Since you were meeting people, the quality of the analysis went down to five.

Now your overall effectiveness:

5 X 6 = 30

It’s a simple principle, but you have to remember that analytics is really not just about analytics itself. It’s about acceptance and effectiveness and, most importantly, the actions that people take after reading your analysis.

That should do it, right? We have great products. We have great ideas. We have great acceptance. We are almost there.

You still need the third P: Passion.

3.3 Passion

It’s not only the passion you have about your analysis, but it’s the passion you show while communicating your results to others.

Steve Martin once said, “Be so good that they cannot ignore you.” In nature, if you stand out, chances are you will get noticed and most likely be eaten. In our world, however, if you get noticed, you will likely get rewarded for your efforts. That will help you sell your analytics and build your authority. Once you have stood out enough times, your consistency and reliability will help build quality and authority. Authority will do wonders for you—whether it’s your career or an analytics project.

Have you noticed that when interviewing people you know within the first five minutes if a person is a good candidate? According to a study, the first 20 seconds of an interview decide the outcome (Prickett, Gada-Jain, and Bernieri 2000). Why does this happen? If the technical competence is equal among candidates, interviewers make biased decisions using presentability as a criterion.

One tool that you can use to become really exceptional is given in the book Innovation You by DeGraff (2011). When you look at your investments, you’re very careful about spreading your risk. But when you look at your own time, you may not be doing so. Lost money may come back, but lost time will never return. DeGraff encourages you to think of your life as an investment portfolio. You diversify your time to learn and do different things. When you diversify your knowledge base, you become exceptional.

Let’s say you want to become a stand-up comic. Don’t quit your day job yet. You put 5% of your time gaining those qualities and, maybe, after six months you look at what happened: what worked better and what did not. Then you make additions to your portfolio based on your success. DeGraff also describes four C’s for better diversified time management.

- Collaborate

- Create

- Compete

- Control

Collaborate is when you are working with other people trying to find something. Create is when you are coming up with some new ideas; you are building something and you are learning something for the first time. Compete is when you are really going out there and building something new. Control is when you give up or reduce something.

Maybe you want to volunteer and so you put 50% of your time volunteering at a local non-profit. Five-percent of your time goes towards your goal of becoming a stand-up comic. After six months, you reevaluate and control your choices.

3.4 Storytelling

Storytelling can really show your passion. Think about your own presentations: do you present your analysis in a meaningful way, or do you show off the fact that your model predicted the tenth percentile of your donors with a 93% accuracy?

You have to think about your audiences: what’s in it for them? Do they care? Do they want to listen to you?

You should think about all these things before you even open up PowerPoint. Maybe you don’t even need PowerPoint.

P. Smith (2012), in his book Lead with a Story, gives an example of when storytelling wins over data:

There was once an advertising manager. He wanted to show that his client’s competitors were outperforming his client. He collected all the data and produced beautiful slides and charts, but the night before the meeting, his boss told him not to use any slides.

The manager was really disappointed because he was proud of the hard work that went into creating his branded bar chart. But then he grabbed a newspaper. He got his son’s yellow star stickers and put those stickers in front of his client’s ads and his competitor’s ads. He took this newspaper the next day to the meeting and handed it to an attendee and asked him to count the stars. The attendee counted, “one, two, three,” for his own company and, “one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine” for his competitor. Three times more ads for their competitor. Do you think a bar chart would have created a better impact? The message of this exercise stuck with this audience—much more so than the bar chart would have.

We like to think that we are rational people, but we make many decisions driven by emotions and biases (Kahneman 2011). If that were not true, we would not purchase more expensive products instead of the generic brand (containing the exact same ingredients) for the hundredth time. Ultimately, you have a better chance at succeeding if you have a good story to tell and can tap into people’s emotions. You should consider this before you present your next analysis.

In summary, there are three P’s to increase your chances of success in analytics: build great products, understand people, and show your passion.

References

Colvin, Geoff. 2009. Talent Is Overrated. Findaway World.

Porter, Michael E. 1996. “What Is Strategy.” Published November.

Stadtler, Hartmut. 2015. “Supply Chain Management: An Overview.” In Supply Chain Management and Advanced Planning, 3–28. Springer.

Heath, Chip, and Dan Heath. 2007. Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die. Random House.

Holte, Robert C. 1993. “Very Simple Classification Rules Perform Well on Most Commonly Used Datasets.” Machine Learning 11 (1). Springer: 63–90.

Amblee, Naveen, and Tung Bui. 2011. “Harnessing the Influence of Social Proof in Online Shopping: The Effect of Electronic Word of Mouth on Sales of Digital Microproducts.” International Journal of Electronic Commerce 16 (2). Taylor & Francis: 91–114.

Bore, Inger-Lise. 2011. “Laughing Together? TV Comedy Audiences and the Laugh Track.” The Velvet Light Trap, no. 68. University of Texas Press: 24–34.

Cialdini, Robert B. 1987. Influence. Vol. 3. A. Michel Port Harcourt.

Voehl, Frank, and H James Harrington. 2016. Change Management: Manage the Change or It Will Manage You. Vol. 6. CRC Press.

Prickett, Tricia, Neha Gada-Jain, and Frank J Bernieri. 2000. “The Importance of First Impressions in a Job Interview.” In Annual Meeting of the Midwestern Psychological Association, Chicago, Il.

DeGraff, Jeff. 2011. Innovation You: Four Steps to Becoming New and Improved. Ballantine Books.

Smith, Paul. 2012. Lead with a Story: A Guide to Crafting Business Narratives That Captivate, Convince, and Inspire. AMACOM Div American Mgmt Assn.

Kahneman, Daniel. 2011. Thinking, Fast and Slow. Macmillan.

Using the 80-20 Pareto principle, 20% of the readers will finish this book and even a smaller percentage will actively practice.↩

Wharton Professor Karl Ulrich on innovation: https://youtu.be/ZSZ6WjwB9g8↩